Why Yellowstone is the most Anti-Woke Show in Existence

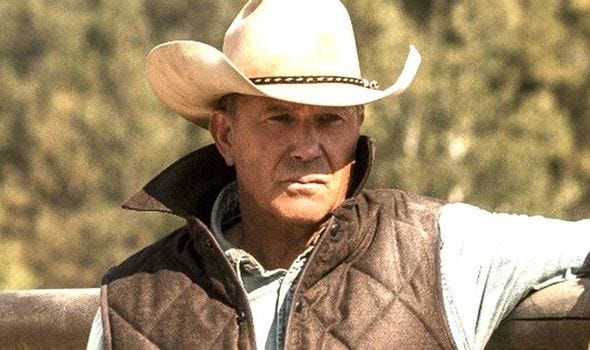

If you’re missing “Yellowstone” on Paramount, you are missing the best television since “The Shield,” “The Wire,” or “Sons of Anarchy.” Hatched by Taylor Sheridan and starring—-more or less—-Kevin Costner, this is anything but “Dallas” for the 21st century.

The Dutton Yellowstone Ranch in Montana (though much is filmed in Utah) is the domain of patriarch John Dutton (Costner) who runs the ranch through his sons, Lee (who is also an agent of the Montana Livestock Commission and head of Yellowstone security), Jamie (a lawyer, family black sheep in his inability to evoke any connection), Kayce (former Navy SEAL, married to Monica Long, a Sioux), and Beth (a mergers and acquisitions financial genius). At one point or another, John puts each of the kids in key political/financial posts in Montana to protect the ranch.

Lee (Dave Annabele isn’t around long enough to learn the ranchhands’s names. He is killed in the first episode by Monica’s brother in a shootout on the rez over stolen cattle. The producers virtually wrote Lee out of existence after his burial. John never mentions him or mourns him; but rather immediately begins to weigh the advantages and disadvantages of turning the ranch management over to either Kayce (Luke Grimes) or Beth (Kelly Reilly). In his heart, though, John knows neither of them is truly suited to managing Yellowstone.

(Jamie on left, Kayce and Beth on right)

Kayce’s heart is with Monica, and that means he has one foot on the rez most of the times (she has both feet there all the time). Beth actually hates the ranch, and has told John that when he is gone she would burn it to the ground. Of course, Beth is a tad unstable, and a heavy drinker.

That really leaves Rip, the cowboy foreman (Wings Hauser) in what has to be Hauser’s role of a lifetime. Rip is the man every man wants to be. He is tender with Beth, whom he loves, and later, you see he can be patient with the child (“Carter,” played by Finn Little) they take in when he is orphaned by the overdose death of his dad. By season four, it’s looking increasingly like John will have to ignore bloodlines and turn the ranch over to Rip as he and Beth plan marriage.

Yellowstone stands out as anti-PC and anti-woke at almost every turn. John, Kayce, and Rip are all fair, just, and decent—-till you cross them. If you attack the ranch, you’re done, and each of them can be thoroughly ruthless. If cowboys on the ranch are beyond redemption, they get sent to the “train station,” which is to say a deserted stretch of mountain road where they are dispatched then nudged down the canyon. Few go to the “station” and return. One notable exception is ex-con Walker whom Rip recruits—-but who has so many problems fitting in he is headed for the station until he is shown mercy and told not to come back. But he does. And soon becomes a key character.

The central battle of the Yellowstone series involves protecting the ranch’s land against greedy business developers who want to build resorts, golf courses, and airports for tourism. Any one of these has more money and resources than Dutton, who is finding cattle a declining business. Jamie keeps trying to find ways to sell parts of the ranch to protect the rest of it, which drives Beth’s antagonism of him into pure hatred. Indeed, Jamie’s character is the only weak spot in the whole cast over four seasons. Sheridan and the writers have managed to fill each cowboy, each Indian with several layers of complexity. And at times, the Sioux and the white man are allies; at other times, enemies. In this, Chief Thomas Rainwater (Gil Birmingham is terrific, as is his second in command, Mo (Moses Brings Plenty). Despite some over-the-top rhetoric (largely, one thinks, for internal Sioux consumption) about taking back the land from the white man, Chief Rainwater and Mo both seem to understand that the world is never going back, and they make more than a few accommodations to work with Dutton and Kayce.

Indeed, the underlying theme is that reds and whites can work together to improve the lives of each, protect the environment, and still respect the fact that man must be a warrior. A key scene on this topic involves Rainwater and Monica, Kayce’s wife (Kelsey Asbille). A group of hired killers (whose boss remains a mystery) tried to kill Dutton, Beth, Kayce, and all the ranchhands simultaneously while Monica and her son Tate (Brecken Merrill) were at the house. Just as the killer draws a bead on the helpless Monica, Tate picks up a loose gun (of which there are plenty in the Dutton household) and blasts him to the Cheyenne rez. But the killing traumatizes Tate, who is only finally brought out of it by going back to the rez in a “smoke out” where he undergoes a Sioux smoke tent treatment.

As Tate exits, Rainwater tells Monica that the world is filled with sheep. They need to stop looking for the shepherd and learn how to become warriors who can defend themselves. This is a welcome message in the China Virus age, where the masked dutifully walk around like Rainwater’s sheep.

In another exceptional exchange, John Dutton encounters an environmental-whacko protest in town. He suggests the sheriff arrest the ringleaders, including Summer Higgins (Piper Perabo). But, Dutton has compassion on Higgins and pays her bail, asking her if she would like to see his ranch. On the drive to Yelllowstone she comments about him killing animals to eat. He asks, “Have you ever plowed a field to raise quinoa or soy or whatever the hell is you eat?” He then points out that merely plowing a field kills mice, snakes, frogs, and dozens of other critters under or just on top of the soil. “How cute does an animal have to be before you won’t eat it?” he asks. Higgins is dumbstruck, and has no answer. Later she sees him and Rip rescue a calf caught between strands of barbed wire fence. She realizes that while cattle ranching is a business, it is, to quote Elton John, part of the circle of life.

Still later, Beth encounters Higgins back in in the street protesting fur wearers. Taking her aside, Beth explains Higgins is having absolutely no effect. If she really wants to save the environment, maybe she should stop the airport construction or the new golf courses.

Both John and Beth preface their “aha” moments with Higgins with predictable “yes, the environment is under attack” kinds of phrases, but the fact is John sees cattle raising as living in harmony with nature; Beth could care less about the environment—-she is just pushing buttons with the hapless hippie.

I could go on: Beth, while a feminist, becomes putty in Rip’s hands; Rip, after tough love, teaches Carter the necessity of tying the right knot; and Walker and one of the long-established cowboys, Lloyd, engage in a brutal fight at Dutton’s demand so that they get it out of their system. When the fight is over, Lloyd buys Walker a new guitar to replace the one he destroyed. In a touching scene, Walker (who sings like a real cowboy probably would sing, which is to say, poorly) nevertheless sings a song that essentially speaks to all their difficult relationship on the ranch and in nature itself.

Every step of the way Yellowstone reaffirms masculine values without diminishing true femininity; preaches environmental protection within the necessities of sustaining human life and growing communities, and celebrates the fact that Indians and whites don’t have to be the same to have the same hopes and dreams.

And so far, not a single LGBTQXYZ character on the horizon.

Larry Schweikart

Rock drummer

Film maker

NYTimes #1 bestselling author

Political pundit

For even more truth-based current events, politics, and history content + resources, check out my VIP membership below

https://www.wildworldofhistory.com/vip