I know, I know. Martin Scorcese. Ron Howard. Steven Spielberg. Do I hear Michael Bay? Going once . . .

Face it. Clint Eastwood is America’s Director. Other guys make good, even fantastic individual films. But Clint’s life—-and especially his director’s legacy—-is a love poem to the United States and her values. While the others tell stories to tell stories, Eastwood makes movies to honor the soul of America.

As an actor he personified the “fewer words, more action” man. When he said something, it had a point. It wasn’t endless ruminating about his navel. As a director, he led us through a wild panorama of subjects that always had that Americana touch.

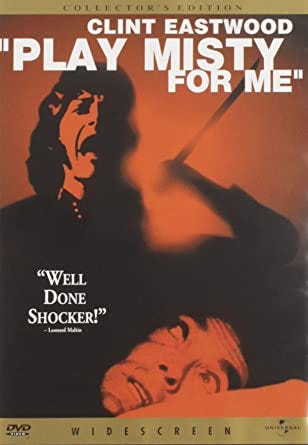

Starting with “Play Misty for Me” in 1971, Eastwood flipped the script with an obsessed female fan terrorizing a disc jockey. Two years later, he directed the first of a series of similarly-themed westerns, “High Plains Drifter.” In this and “Pale Rider” (1985) and to an extent even in “Unforgiven” (1992) which was the first of his four Best Director Oscars, Eastwood continued his “man with no name” persona. He captured capturing the deep-seated American yearning for justice, especially against crimes carried out by the powerful against the weak.

But Eastwood did not settle for turning out formula pics, and certainly “Unforgiven” was no run-of-the-mill Western. It explored the sadistic sheriff (Gene Hackman), the gunslinger whose time had passed (Richard Harris), the reluctant heroes (Eastwood and Morgan Freeman), and above all, the wrong that needed justice. Remember, “he shoulda armed himself.”

As Eastwood explored more dense subjects, such as his second Academy Award for directing (“Mystic River,” 2003) he dealt with the impact of sexual abuse on children, then on assisted suicide in his third Oscar winning directorial performance (“Million Dollar Baby,” the following year), and then, just two years later, the impact of combat on ordinary men deemed extraordinary by a single act (“Flags of Our Fathers,” 2006).

This was perhaps the one big exception in all of Eastwood’s movies in that more than any other it required a large cast and vast CGI support for the Iwo Jima invasion shots. But that really wasn’t Eastwood’s stock and trade, as seen by the companion movie (the only time he really left American soil philosophically speaking), “Letters from Iwo Jima,” which was mostly a personal reflection of the Japanese enemy.

Some of Eastwood’s reluctance to work with “big scope” pictures may stem from his reported on-set discipline of obsessive preparation, then shooting as few takes as possible. Such is not possible with massive “Ten Commandments/El Cid” type sets.

That’s not to say he doesn’t have big backdrops, as he did with “Invictus” (2009) or “Sully”(2016). His focus, however, is the individual. How did “Sully” Sullenberger cope with both the success of landing a plane in the Hudson River without losing a single passenger while knowing that he was possibly just seconds from flying his jet into a skyscraper?

In 2008, he had another pair of powerful films, either of which could have won an Oscar: “Changeling” and “Gran Torino.” Eastwood showed in “Changeling” that he he could challenge the establishment/the system in the form of the L.A. Police Department and their abuse of a woman whose son was abducted without attacking the notion that police—-good, honest police—-are needed. “Gran Torino” told the story of an aging man hardened by the loss of health, his family, and the transformation of his neighborhood. Yet he slowly befriends his Hmong neighbors to the point that he ultimately sacrifices himself for them.

The last, or more appropriately perhaps, the latest, of Eastwood’s Oscar-winning performances, “American Sniper,” did not win him another Best Director award, but did win Best Picture. Again, the focus was not on the war in Iraq, but on the pressures that tormented sniper Chris Kyle into returning to action again and again. Kyle is a hero not only because he fought, but because he defeated his own demons—-only to be killed by someone else struggling with the exact same PTSD issues.

Eastwood, perhaps more than most directors, takes significant chances, none more so than casting the three American boys who stopped a terrorist attack on a Parisian train in the lead roles (“The 15:17 to Paris,” 2018). His emphasis was that the American youts were ready, willing, and able to do what many French were not in confronting evil aboard the train.

Perhaps Eastwood’s biggest failure was he take on “Jersey Boys” (2014) which, while the story of Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons, was more a character study of obligation when Valli toured constantly to pay off a gambling debt for bandmember Tommy Devito. Despite being a musician himself, Eastwood never quite captured the bolt and buzz of a successful musical movie. Nevertheless, once again the subject was American loyalty and friendship, even if it comes at great personal cost.

No matter. Eastwood then moved into a trio of rather introspective films that collectively showed that even in old age, he had a tremendous amount of insight into the American character—-and into himself. In “The Mule” (2018) Eastwood told the story of a failed horticulturalist-turned-drug-runner. Part of Earl’s appeal comes from the fact that at his age, the Sinoloa Cartel really can’t threaten him with too much. Once imprisoned for his crimes, he returns to the life of flowers that he left. Having filmed courageous young people with a great deal to lose in “Flags,” “American Sniper,” and “15:17,” Eastwood goes the other direction to show courage in old age.

In between “The Mule” and his second character study of an old man on a mission, Eastwood took on one of the biggest injustices of our day, the public media-lynching of security guard Richard Jewell in “Richard Jewell” (2019). Were he to take on the subject of the Patriot Day (January 6) prisoners, I’d bet he would tell the story much the same way. Out-of-control government authorities, wed to a predetermined verdict, pushed aside all evidence to pursue their victims.

His most recent film, “Cry Macho” (2021) returns to the theme of an elderly man sent on a mission to return a man’s son to him from Mexico, where his employer can’t go personally due to legal difficulties. Eastwood, the boy (Edwardo Minett as “Rafo”), and a rooster named “Macho” have to overcome the Mexican cartels, the Federales, and other obstacles to return the boy to his father. In previous eras, Clint’s character Mike Milo would have shot or fought his way out. But that’s not longer an option for the aging Eastwood. Now he has to acquire victories by other means. He uses his wits, his grit, and occasionally his charm to transport Rafo to the border—-with a little help from Macho. Once again the subject is justice—-justice for the father, but also justice for Rafo to have a better life. One that he legally is entitled to.

Although Eastwood floats from the South Pacific to Mexico to Los Angeles to Paris to the Wild West, he always keeps the focus on those things that speak of the best in Americans—-courage, justice, mercy, sacrifice, and honesty. It’s highly likely that when he finally folds his director’s chair, Clint Eastwood will have as a director eclipsed his work as an actor-icon (with “Man With No Name” and “Dirty Harry,” two classic characters) many times over. And he will have done it by turning his camera on America.

Larry Schweikart

Rock drummer

Film maker

NYTimes #1 bestselling author

Political pundit

For even more truth-based current events, politics, and history content + resources, check out my VIP membership below

https://www.wildworldofhistory.com/vip

With my director Marc Leif at the LA opening of our film “Rockin’ the Wall” circa 2014.

As much from the heart as from the history books. Cheers.

My issue with Gran Torino was it was basically a remake of The Shootist, and The Duke is still The King!