Recently a breakthrough in fusion power was announced. This may be “something,” may be “nothing,” but this was the first time anyone has ever gotten more power out of fusion than they put in. Helion, a company that has kept this under wraps for years, no doubt has received gubment money. But what’s interesting is that it’s not Westinghouse, General Electric, or any well established nuke power provider or energy company.

Most likely, if fusion is to ever “make it” as a useful energy source, it will be more unknowns who run with it, tinker, develop some unique but probably obvious way to harness it. Sometimes it just takes someone else learning about it.

Consider John Fitch, the guy who invented the steamboat.

No, not Robert Fulton.

Fitch beat Fulton by 12 years at least, and had monopoly rights to carry traffic and freight on the Delaware River. As one biographer said, though, “He picked the wrong river.” The Delaware was easy to sail and had roads running alongside. Fitch couldn’t beat the competition. When his last boat wrecked, he took opium pills and committed suicide.

Fulton learned of Fitch’s vessel and imagined—-for he was very good at imagining!—-a steam powered boat on the Hudson, which was a tougher river to navigate and had fewer roads. In essence, Fulton’s Clermont was bigger, niftier, and much better marketed than Fitch’s paddle wheeler. Fulton was just the first of many to show that the leader in the field, almost any way you choose to apply your definition, seldom makes the next great breakthrough.

Consider land transportation in the late 1800s: the major land mail- and passenger-haulers (other than railroads) were stagecoaches: Overland, Wells Fargo, and Adams Express coach companies. Yet the big breakthrough in road-based ground transport came not from them, nor from the railroads, but from a guy at Westinghouse, Henry Ford (and yes, many others were tinkering with steam-engine cars at the time including Daimler in Germany). If you really want to argue about “who invented the car,” you can take it up with my former colleague at the University, Professor John Heitmann who wrote The Automobile in American Life.

Well, how about air travel? In the late 1800s, balloons were “it.” Yet it was not a balloon manufacturer who led to controlled, powered flight but two brothers working on bicycles in Ohio.

Yes, there were also glider forerunners, including Richard Gatling—-inventor of the Gatling gun, who crashed his only test glider.

And yes, Samuel Langley, an architect and astronomer, was hot on the heels of the Wrights, though he was funded by the U.S. gubment, while the Wrights—-for some time—-were on their own.

How about the leader of the pack in computations? That would have been Keuffel’s slide rule. Did Keuffel invent the computer?

Whether you say Charles Babbage, Alan Turing, Texas Instruments or International Business Machines (IBM), it wasn’t the leader in the field. And when IBM went on to dominate the world, selling 85% of all large computers, it came up with the idea for a smaller, desk-sized personal computer, right?

Er, no. That would be Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.

And in the 1990s we all walked around listening to portable music from this, which, at best, gave us 12-20 songs:

Of course, the real revolution did not come from Sony, or Electra, or Warner Bros., or Arista, or Columbia, or Capitol, or any of the major music/record companies, but from our old pal Steve Jobs—-a computer geek.

Why?

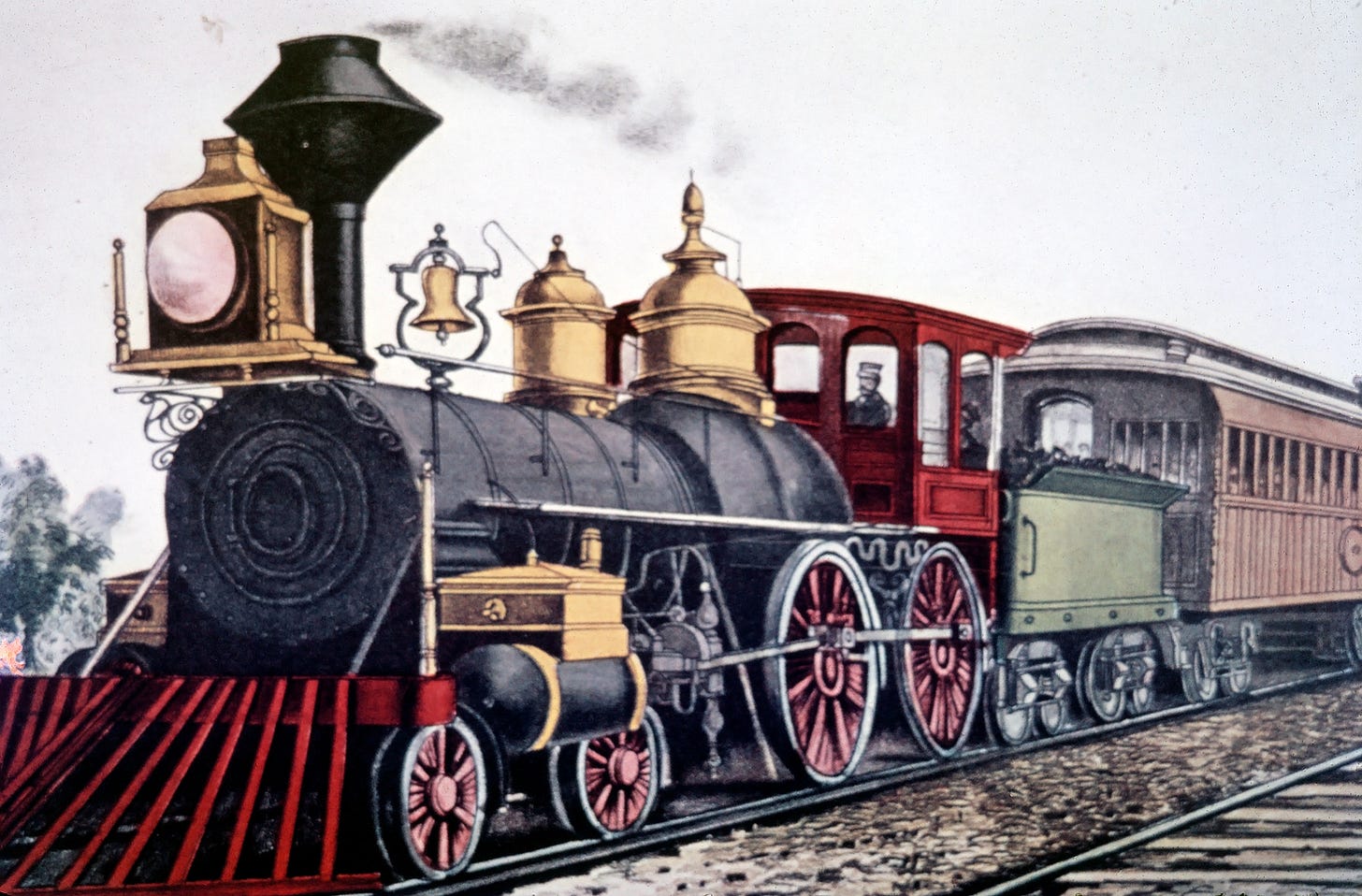

In his 1977 Pulizer Prize winning book, Visible Hand, Harvard Professor (yes, they do make contributions once in a while) Alfred Chandler led the reader through a long history of the . . . railroads. It was there that this principle first took hold because, you see, railroads weren’t cheap!!!

Their capital demands were 10 times per railroad more than any other business. In fact, the top ten railroads were all more expensive than the #11 business in the country, a textile mill. Raising vast amounts of money required something we now know as selling stocks, or ownership, in the railroads. But now, instead of one owner-operator, you had hundreds, maybe thousands. Who would run the company?

Increasingly the answer to this was a professional. Someone that all the stockholders could trust that “knew his stuff.” And to prove he “knew his stuff,” he had to have training and experience. Thus professional managerial schools were born—-business schools—-and the graduates came out with a stamp of approval. They had not built any railroads themselves. Indeed, most had never laid a single tie or rail. But they knew the numbers and in the evolving business climate, that was important.

Really important.

These professional managers became a permanent fixture in American industry by the late 1800s. Increasingly they worked their way up through the “finance” side, i.e., raising money and counting costs, not through the production side where stuff was actually made.

By the 1950s, most of the big companies had already been taken over by the “finance men.” This story is never told better than in David Halberstam’s book about Ford, The Reckoning, where a name from the past, Robert McNamara, came up through the “finance” side to take over Ford and many would say, nearly destroy it.

Above all, the new “finance men” were terrified by sudden and uncontrolled stock movement. Their goal was a nice steady line rising to the right, say, at 2%-3% per year. Sure, you might jack that line up a lot with a really risky venture, but if it doesn’t pay off, your company may go belly up. (This almost happened to IBM under Tom Watson, Jr. who “bet the farm” on the new 360 computer). Thus wild innovations that may actually constitute huge breakthroughs just have too much risk.

Most of you are too young to remember the “new models” of cars rolled out every year, where the really big changes were . . . different fins. Rear engine drive? Are you kidding? Disc brakes? Who needs those? Fuel injectors? Carburetors are just fine, thank you.

Detroit, as Halberstam showed, threw open the door to Japanese and European competition by refusing to adapt because major changes rocked the boat for that 2%-3% increase.

Whether Tesla (or any electric vehicle) truly “makes it” without gubment subsidies remains to be seen. But you gotta give ol’ Elon credit. He wasn’t an “inside job.” He made his money in computers, then PayPal, then SpaceX before electric cars. Once again, the big breakthroughs come from anyone but the leader in the field.

It’s baked into the cake.

Larry Schweikart

Rock drummer

Film maker

NYTimes #1 bestselling author

Check out my new Master Class in US and in World History at https://www.wildworldofhistory.com

Loved that show, though he took liberties.

I always enjoyed James Burke's "Connections" shows. They illustrate how almost every great invention or discovery were generally "accidents" that came about by someone making a connection between an existing technology and applying it in a way that wasn't ever imagined by the original creator. It makes the hubris & fatal conceit of government thinking it can create things by top-down decree even more jaw-dropping. (example: deciding that by throwing billion$ around among the legacy players, a better battery will be invented, or Biden's "Cancer Moonshot" - parts I & II)