Japan and the End of World War II

Had the Emperor not reluctantly stood up to the warlords, Japan would not exist today

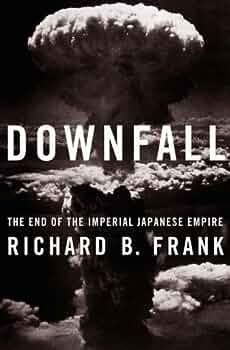

I just finished reading a great, great book, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire by Richard Frank. While generously soaked in statistics, casualty numbers, and bombing effectiveness ratios, this is a necessary read for anyone ever wishing to dispel the idiotic notion that Japan would have surrendered without the atomic bombs.

Frank meticulously lays the groundwork for this work by reviewing the decision-making of the inner circle from both Japanese and American documents. He notes that the “Big Six” council that presented the Emperor with options (the “Supreme Council for the Direction of the War”) consisted of the premier, the foreign minister, the Imperial Army minister, the Imperial Navy minister, and the Chief of Staff of the Army and Navy. Thus Japan’s leadership was 2/3s military, and that military was absolutely rabid in its warrior “bushido” ethos.

It is first critical to understand that in Japan herself, the U.S. had been staging vastly more lethal raids than either atomic bomb for some time. The firebombing of Tokyo beginning at midnight, March 9, 1945, left the city flattened and killed 100,000. By that time, Japan had completely given up on offensive operations, even in China, where a 300,000 man army was stationed. Instead, the Japanese were carefully rationing fuel and metal to build suicide weapons for Ketsu-Go, the “decisive” battle for the homeland.

Japan’s military and its civilians were preparing for national immolation and suicide. Vast numbers of civilians were being dragooned into service to learn how to pilot small explosive laden mini-subs to kill themselves and a U.S. ship; to detonate bomb harnesses in the midst of Americans; and how to fly the new Baka bomb planes (these were simple and contained enough explosive in the nose to sink a ship. Point and explode. “Baka” meant “cherry blossom” but Americans called them “stupid” bombs.

Based on expectations that the Americans would first invade Kyushu, then Honshu at the area of the Tokyo plain, Japan had transferred far more troops to the island than Americans expected, to the point that ULTRA/MAGIC codebreaking intercepts showed that at the time of an invasion (“CORONET”) the ratio of defenders to invaders would be a fatal 1:1. (Generally it is assumed a military needs three times the number of attackers as defenders, but that is against a rational, western army that surrenders: the Japanese simply refused to surrender.) As the MAGIC decrypts poured in, American invasion planners went white at the thought of spectacularly high casualties.

But ULTRA/MAGIC were bits and pieces. Confirmation came as the Americans drew closer, when actual photographic reconnaissance showed (as ULTRA predicted) a shocking 1,800 suicide planes in Kyushu alone, and a staggering eight thousand suicide planes in Kyhusu, Nagoya, and Tokyo. A single kamikaze had taken out entire aircrafte carriers, killing hundreds of sailors before a single Marine set foot on an island at times. The thought of the impact of 8,000 such kamikazes would make for staggering reading in U.S. newspapers. A conservative estimate put the casualties from Kamikazes alone at nearly 13,000.

Great controversy over how many Americans would have died and been wounded if the two invasions, CORONET and OLYMPIC (Honshu and Tokyo), went forward. While they shouldn’t be, these numbers became a point of argument for moronic leftists arguing that “Gee, our casualties wouldn’t have been that bad without the Bomb. We should have just invaded.”

In my view, ONE unnecessary American death was too many by that time.

As Frank shows, the debates within the Joint Chiefs and the Department of Defense over the exact cost of invading Japan were riddled with misconceptions, incomplete data, and flat out silliness. Mostly, they were based on the invasion of Luzon (which Gen. Douglas MacArthur used as a frequent touchstone for extremely low casualty estimates) to Okinawa and Iwo Jima. But even when the latter (more accurate) estimates were employed, they never, ever included naval personnel lost to kamikazies, accidents (which account for a LOT of deaths), air crews (which had suffered substantially, though by August 1945 the losses had fallen precipitously), and other non-combat troops. These way, way low estimates were shocking enough by themselves. But had all casualties at all levels been included, then the projected combined two-island casualty totals were a staggering 1.2 million based on the Pacific invasions so far. (The U.S. had, by that time, already lost 87,000 dead in all theaters.)

And the 1.2 million casualty estimate? That was just for a 90-day campaign. If the Japanese held out longer . . . .? Admiral Nimitz produced an estimate that there would be almost 50,000 killed and wounded in the first 30 days; MacArthur, predictably, came in at about half that. In a key meeting in June 1945, President Harry Truman was apprised of a number of 100,000 casualties—-a number that George Marshall tried to quash. Truman was still overwhelmed by even the lower estimates. Still, according to Frank, Truman “when he was never given a firm number and denied access to a number of sobering estimates,” did not veto operation OLYMPIC. The invasion was planned.

Amidst all this, lost was the impact such an invasion would have on Japans’s (semi) civilian population. The few estimates that were produced came in at between 1.5 and 10 million.

Put another way: the a-bombs likely saved over 100,000 American dead—-or more than the entire war had taken up to that point—-and up to ten million Japanese. The bomb was a powerful life-saving tool in the long run .

To gauge the mindset, after the Hiroshima bomb, Dr. Nishina, Japan’s top atomic scientist was sent to the site to determine if it was an atomic bomb. When he answered affirmatively, the leaders asked, “How long before we could build one?” Of course, they couldn’t. Japan was not within years of an atomic bomb, even if they had the uranium, which they did not. Their first response to the call for surrender in the Potsdam Declaration was “utter contempt” as one translation put it.

By August 9, faced with a new problem—-the Soviets finally entered the war against Japan in China and routed Japanese forces—-the Big Six met again with the Emperor after the Nagasaki bomb. Up to that point they held out for the possibility that Ketsu-Go would so bloody the Americans and seep their morale that they would agree to something less than “unconditional surrender.” Now faced with the prospect that the U.S. had a pipeline of A-bombs, the militarists held out, but others insisted there would be no better terms than unconditional surrender as stated in the Potsdam Declaration with an amorphous reference to the Japanese selecting their own leader (presumably including the Emperor). Though few among U.S. leadership liked it, most agreed that the Emperor would be key to disarming the entire Japanese population and ensuring their compliance.

The Emperor Hirohito overruled his military leaders when they told him the war in China was lost. “We must bear the unbearable” he said, and without ever saying “I surrender,” the Emperor sent a cable through neutral parties that Japan accepted the Potsdam Agreement.

Americans were still wary. Japanese leaders had been assassinated before when they crossed the warlords. And they tried again, but failed to reach the Emperor’s inner compound, whereupon the ringleaders all committed hari kari. Japan officially surrendered on September 2, 1945. Thanks to the atomic bombs, hundreds of thousands of Americans and millions of Japanese lived.

Larry Schweikart

Rock drummer, Film maker, NYTimes #1 bestselling author

For even more truth-based current events, politics, and history content + resources, check out my VIP membership below

https://www.wildworldofhistory.com/vip