"Napoleon: A (Failed) Love Story"

Like Christopher Nolan and "Dunkirk" before him, Ridley Scott's material overwhelms him.

As a historian, I’m always excited to see a history-based film come out. Unfortunately, they almost always let me down. The last truly great military/action history film was “13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi.” Obviously there have been fantastic drams such as “Darkest Hour.” But getting battles right seems a, pardon the pun, bridge too far for too many of these giants.

Consider “1917,” which struggled to offset the horror of trench warfare with a “Private Ryan” type quest, or “12 Strong,” which could not properly frame the conflict to elicit strong emotions. Is the world just more sophisticated? Or have movie-makers lost their way?

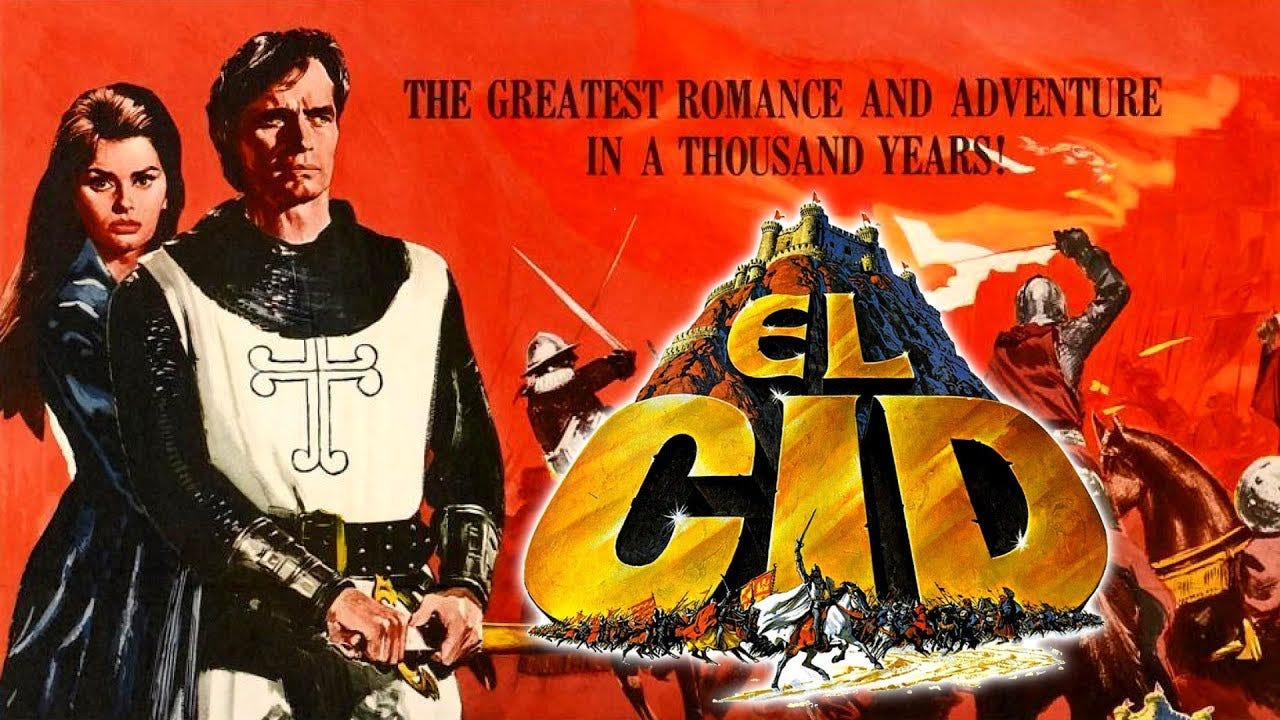

“Napoleon,” Ridley Scott’s new epic about Napoleon Bonaparte—-easily one of the most interesting figures in all of history as judged by the number of books written about him (more than anyone except Jesus) promised a return to non-CGI battles and, one would hope, deeper storytelling. It somewhat succeeded on the first mission, failed entirely on the second. On the ride home with my 35 year-old son, he said, “Why can’t these guys make ‘El Cid’ anymore?”

That was a very good question. Anyone who has seen “El Cid” (1961) with Charleton Heston and Sophia Loren appreciates what a sweeping historical tale it is. Of course, then as with “Napoleon,” the producers/directors/writers too major liberties with the facts. (El Cid did not die in the Battle for Valencia, nor was he ever strapped to a horse). They didn’t have CGI, though Samuel Bronston did have use of the whole Spanish Army given to him by Francisco Franco because, well, Franco wanted to be seen as El Cid.

“Dunkirk,” which I very much anticipated, was a boring let-down. Rather than focusing on the high-stakes circumstances—-which came across far better in “Darkest Hour”—-Christopher Nolan went all New Art, complete with an ear piercing sound that lasted for the better part of 15 minutes. In the end, you would have thought one guy got rescued, one pilot shot down, and one private boat captain saved the Brit Army.

“Napoleon” however does not lack for scope. Big battles are BIG battles. The most memorable—-and best done===scene is not Waterloo but Austerlitz, where Napoleon sucked in the Coalition armies to a trap then enveloped them. Scott made the horrific scene of retreating Russian soldiers across a frozen lake seem like Napoleon planned it. Instead, the brilliant general as he often did merely adapted on the fly and trained his cannons on the lake, breaking it up under the army. Those scenes are truly horrific, and probably are some of the most anti-war scenes one could ever film.

Otherwise, Scott seemed himself to be drawn under Lake Satschan. First, he undertook way too much chronologically as well as thematically. Napoleon’s career spanned, easily 20 years. This would be akin to Franklin Schaffner trying to tell George Patton’s story from his time at West Point, as opposed to just three years of war. As with “Patton” (1970) Scott attempted to use the battles as backdrops to the more personal story of Napoleon. Yet when the film ended, we still did not know much about him except perhaps (as Scott portrays him) he was semi-autistic. He was not.

Napoleon Bonaparte was a brilliant, bad man. Some aspects of his talents were almost beyond belief. He spent two years in the Topography Department of the French Army. Normally, soldiers would recoil at this assignment, preferring cavalry. But Bonaparte understood that in the late 1700s/early 1800s logistics and movement were even more important than today. Then, one could not air drop supplies, or fly in helicopters full of reserves. Thus Napoleon learned to read maps like no other human. He could, and did, calculate the rates of march for seven corps (well over 100,000 men) over 200-300 miles and predict with uncanny accuracy what hour they would arrive on the battlefield. Scott does, however, correctly capture Napoleon’s fascination with cannons and his career-long advantages with them.

But the real story in this movie is not warfare, but love. Probably a better title of this movie would have been “Napoleon: A Love Story.” Here, again, we have major problems. Josephene’s character is not well defined. At first she is a mercenary using her sexual favors to escape her situation. She rolls her eyes as Napoleon is having sex with her, or, at best, is bored. Yet shortly she not only can’t live without him, but wants to ensure he can’t live without her—-even though he can’t get her to write him a damn letter. When the divorce finally comes (because she cannot bear him an heir) Josephene breaks down to the point that Bonarparte uncharacteristically slaps her to get her to sign the divorce decree.

Of course, all of this plays second fiddle to Joaquin Phoenix’s performance, which could have made it all moot. Yet the same man who pulled off a “Joker” equal to that of Heath Ledger offers up a barely-speaking, cardboard, wooden Emperor. Nothing appears to excite him. Is it true, according to Madame de Stahl, that Napoleon loved no one, and was utterly devoid of emotion? Not this Napoleon who writes love letters like he had an Apple program for it. By all accounts he cared deeply for the army, and his soldiers for him. That isn’t shown except in the retreat from Moscow. Could he be unhinged? Probably, but that really isn’t shown either. In other words, other than Ridley Scott himself, the only person who could have saved “Napoleon,” Phoenix, failed.

Needless to say, and probably on purpose, Scott gets the battles wrong. His Waterloo is an abomination of history. No Napoleon Bonaparte never led a cavalry charge, let alone at Waterloo. No commander, stationed at least a half-mile behind the front line so he could observe enemy dispositions could run down and lead an attack. The key moments—-the Charge of the Scots Greys, the battle over the La Haye-Sainte farmhouse, and Marshall Ney’s idiotic cavalry charge against squares were so badly bungled as to require someone to read David Chandler’s Campaigns of Napoleon to sort it all out.

If you want a great Napoleon movie, see “Waterloo” (1970) with Rod Steiger as a great Napoleon and Christopher Plummer as an even greater Wellington. It was done with close to real-life numbers of troops and followed the actual history without losing a beat. Meanwhile, this is a movie that should be seen once, but no more.

Now will someone please make a good war movie?

Larry Schweikart

Rock drummer, Film maker,NYTimes #1 bestselling author

Check out our wonderful Black Friday offers!

https://www.wildworldofhistory.com/special-offers