(This is the third part of a series on American exceptionalism. Part 1 appeared on “War Room” here today; Part 2 on America’s exceptional language will appear tomorrow on UncoverDC.com).

We think of globalism as a recent phenomena. But it’s got quite a history. This is the subject of a book I’m writing, A Patriot’s History of Globalism: It’s Rise and Fall. First, let me state the obvious: any Christian has to understand that globalism not only will fall, but it must fail. Now, if you’re not a believer, you can let that offering plate just pass on by.

The ultimate failure of globalism is in many ways similar to the perpetual failures of socialism. Every place it is tried, it fails and each time, an excuse is offered: “it’s too soon”; it’s “not the right place”; or the most common, “the wrong people were in charge.”

No, globalism has been tried on countless occasions, and has failed every test. I will discuss just one of them, the Congress of Vienna in 1815—-but really a decade-long attempt to establish some sort of control by elites.

After Napoleon ransacked Europe under the auspices of “Republicanism” for over a decade, the sovereigns and diplomats of the victorious allied countries, often for different reasons, sought to re-establish control through a meeting of the best and brightest. These included Klemens Metternich, the wily Austrian conniver whose entire diplomacy was, Clinton-like, tarnished by his obsession over Wilhelmine Duchess of Sargon. Then there was Czar Alexander himself, who viewed Russia’s role as a Christian movement to re-instill pietism in Europe . . . in between his own frequent, unrelenting flirtations. (His come-on line was his handkerchief, which had an embroidered crown of thorns over his initials: he would pull out the handkerchief and explain the travails and loneliness of governance to an—he hoped—-awe-struck doe-eyed female). Or we have Charles de Talleyrand-Perigord of France, the ultimate survivor/chameleon who navigated the French Revolution, the Thermidorean Reaction, the rise of Napoleon, the abdication of Napoleon and installation of Louis XVIII, the abdication of Louis XVIII and restoration of the Emperor, and the final exile of Bonaparte and re-installation of Louis. To keep one’s head on one’s shoulders during all that took talent indeed. Finally, the least morally suspicious of all these characters was Viscount Castlereagh, who survived long enough to see the Congress’s activities wrapped up, then killed himself with a penknife.

Whereas the American constitution was written by a “an assembly of demigods,” according to Thomas Jefferson, the treaty that emerged from this group of numbmuncher elites was a redrawing of national lines based on expedience, a cobbled-up attempt to ensure France didn’t become a threat again; and an effort to ensure on Russia’s part that no western-Euro state could threaten its border, hence the continued dissolution of Poland.

At any rate, naturally America was left out of all this and the Euros patted themselves on the back that they had prevented future wars. (The next big one broke out in 1870, so you do the math). But what, in fact, had the Congress missed that America possessed?

One member of the Congress, Friedrich von Gentz, said in the summer of 1815 that “Never have the expectations of the general public been as excited as they were before the opening of this solemn assembly. People were confident of a general reform of the political system of Europe, of a guarantee of eternal peace, even of the return of a golden age.

Many historians see what emerged as a lost opportunity. Er, no. It never was an “opportunity” for a “general reform of the political system.” That would mean kings and potentates had to go. It’s sort of like expecting the U.S. Congress to actually “reform” anything.

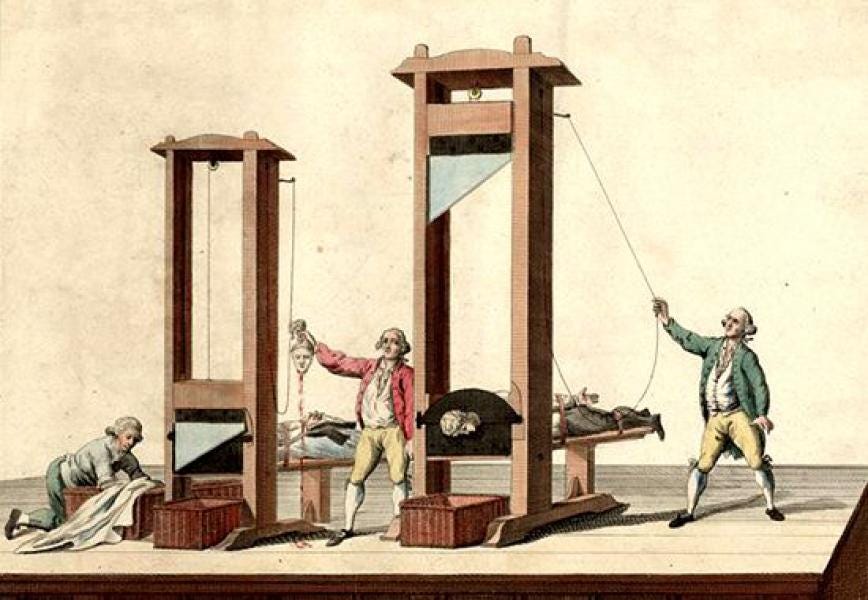

The real reform had occurred in the United States in 1789. It wasn’t perfect, but for the first time in human history it had been the culminating effort of bottom up governance, one of the four pillars of American Exceptionalism. NONE of the Euros had it. The French tried their hand at it, and the result was, well . . .

If you want to know why France hung with Napoleon so long, you need look no further than this.

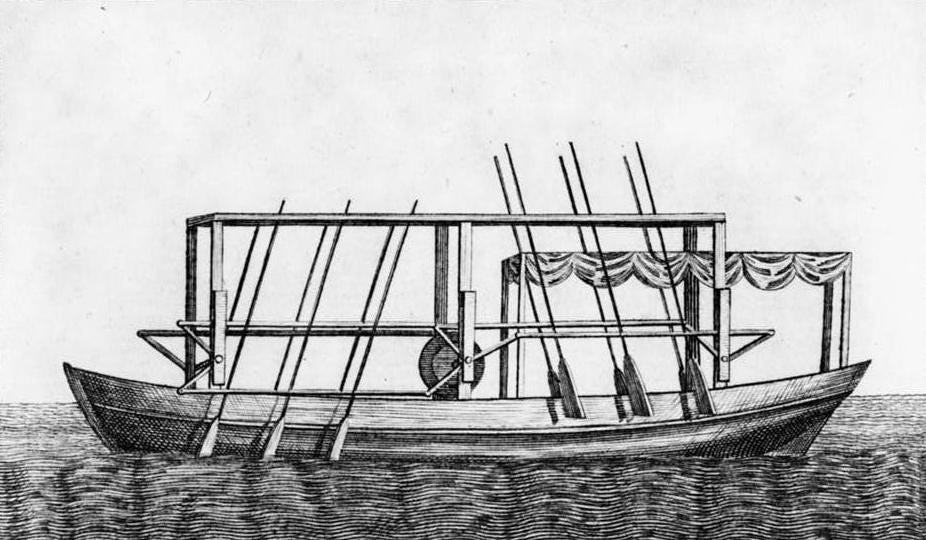

So what the globalists sought was not power to the people but power to the potentates. It was the people who caused all the problems. Unfortunately for the Congress of Vienna, their attempt at globalism (understanding that to them, Europe was the globe) not only failed in its stated objectives of preventing war, but in the perceived objectives of bringing about a better life for the common people. That, it turns out, was effected by more ordinary people making extraordinary inventions, such as John Fitch with his steamboat, or Eli Whitney with his cotton gin, arguably the two biggest inventions of the century between 1790 and 1890, maybe excepting Thomas Edison’s light bulb. Oh, wait . . . those were all Americans, too.

Larry Schweikart

Rock drummer

Film maker

NYTimes #1 bestselling author

Political pundit

For even more truth-based current events, politics, and history content + resources, check out my VIP membership below

https://www.wildworldofhistory.com/vip and take a look at the Black Friday offers. Number 2 features five of my best books, all autographed and shipped, for $114.